A short-fused Babe, a heave-ho and a no-hitter for the ages

Only four pitches into his start against the Washington Senators on June 23, 1917, Boston Red Sox ace Babe Ruth was peeved. At least two of his pitches to leadoff hitter Ray Morgan were strikes, the left-hander thought, but umpire Clarence "Brick" Owens called them all balls.

“Open your eyes and keep them open,” Ruth yelled at Owens, according to the Boston Globe.

“Get in and pitch or I will run you out of there,” screamed Owens, no stranger to confrontations with players or fans.

“You run me out and I will come in and bust you in the nose,” Ruth shouted back. Then the 32-year-old home-plate umpire made good on his promise, tossing the short-fused 22-year-old from the first game of the doubleheader at Fenway Park. And Ruth almost made good on his.

The Bambino rushed past catcher Pinch Thomas, fists flying. Ruth’s left missed Owens, but he connected with a right, just behind the umpire’s ear.

Red Sox rookie manager Jack Barry, Boston players and several policemen dragged their enraged pitcher-slugger from the field. “All season Babe has been fussing a lot,” the Globe reported. “Nothing has seemed to satisfy him.” When he received word of the Bambino’s eruption, American League president Ban Johnson was not pleased: “I’ll take care of Mr. Ruth,” he said.

And thus the stage was set for one of the most unusual gems in big-league history.

On June 23, 1917, Red Sox ace Babe Ruth argued calls with home plate umpire "Brick" Owens (shown) in 1st inning. Incensed, Ruth charged Owen, fists flying, and hit him in the head. He was ejected. Ernie Shore replaced Babe after one batter (a walk) and no-hit the Senators, 4-0. pic.twitter.com/g9zjRdydOm

— john banks (@johnnybanks) June 19, 2020

After a brief warmup, Ernie Shore, who, according to a newspaper account, “has never proved any great puzzle” to the Senators, replaced Ruth. Although the 26-year-old wasn’t as good as The Babe, who was 12-4, he was no slouch. After seasons of 19 and 16 wins, the right-hander was 6-4 with a 1.95 E.R.A.

A graduate of Guilford College in North Carolina, Shore taught mathematics in the offseason. So naturally one of the few college-educated players in the majors was billed in newspaper accounts from the era as the “Professor” or "Prof. Shore."

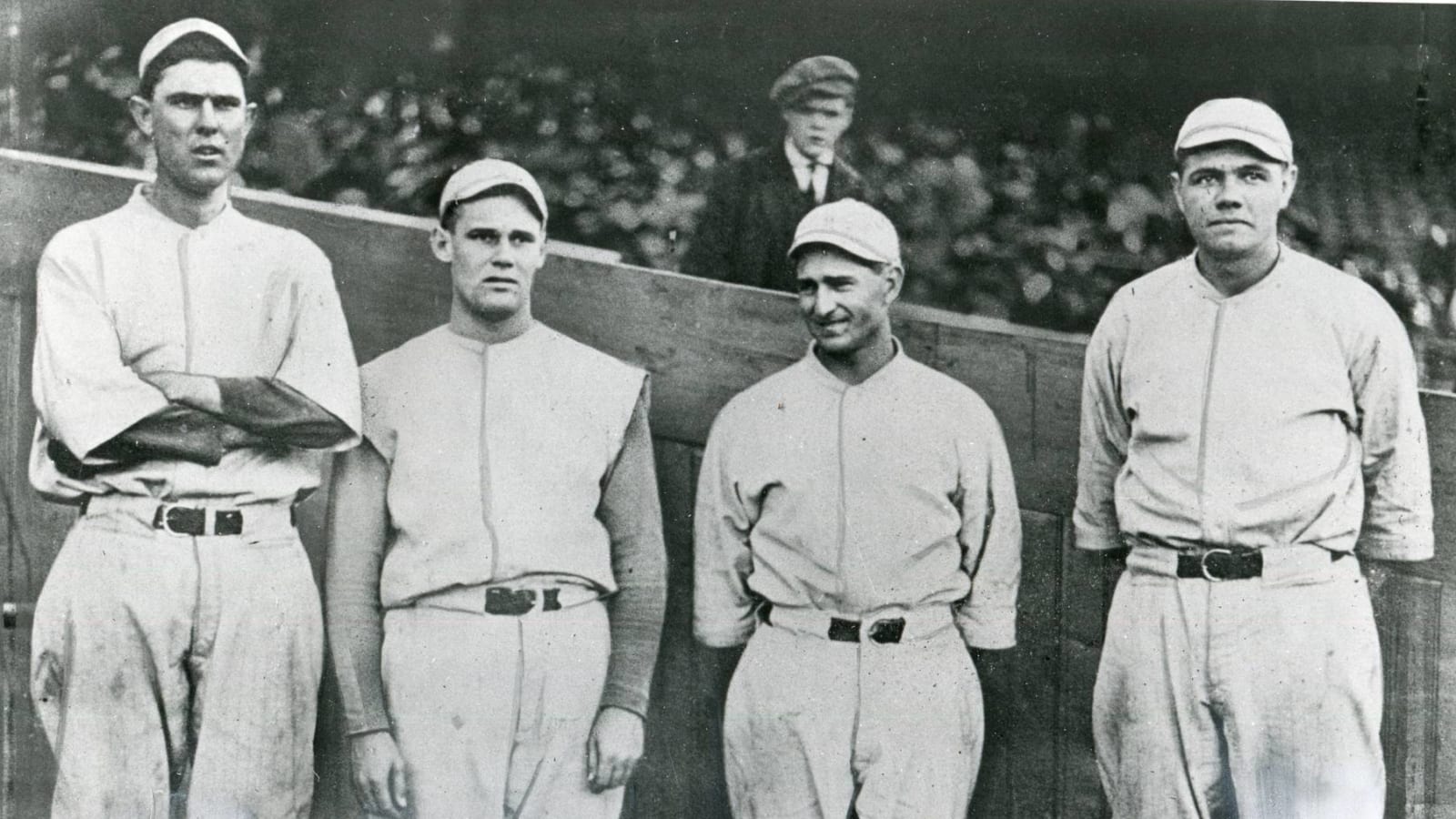

Shore had some things in common with Ruth: Both were big — the Professor was 6-foot-4 and 220 pounds; The Babe was 6-2 and roughly 220 — and each was sold by the minor league Baltimore Orioles to the Red Sox in 1914. Shore even roomed for a time with Ruth, but the mild-mannered North Carolinian apparently was a poor match for the adventurous Bambino.

In the first inning, Shore retired the two batters he faced. (The hitter Ruth walked was thrown out trying to steal second.) The Professor breezed through the lineup in the second, third and fourth. In the fifth, shortstop Everett Scott, “The Bluffton Kid,” fielded a grounder with his bare hand and barely threw out the runner at first.

In the seventh, outfielder Duffy Lewis snagged a long fly ball to left. He was such a master at catching balls on the slight incline near the massive wall in left field -- now called the Green Monster -- that it became known as "Duffy's Cliff." Through eight innings, the Professor had retired the Senators in order.

Shore “fielded his position well,” the Globe reported, “and was ready for any of those cantankerous bunts that the opponents might try to lay down, but strange to say the Griffmen were off that stuff, relying mostly on the slam-bang system.”

Well, OK.

In the ninth, Lewis speared a liner in short left, and Shore retired the side — 26 batters up, 26 down, a "perfect" game with an imperfect start. The Red Sox won, 4-0.

LISTEN: In 1978 interview, ex-Red Sox's pitcher Ernie Shore (left) talked about his no-hitter vs. Senators in 1917. (36:17 mark) Shore shown in 1915 with pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, future Hall of Famer. Photo: Bain collection | Library of Congress https://t.co/r68AuvOxxu pic.twitter.com/HuTqBg3GdS

— john banks (@johnnybanks) June 19, 2020

“Ernie Shore Now Ranks With Best,” read the large headline in the Washington Times the next morning. “Pitches First Perfect Game Since 1808,” read the smaller headline below. (Whoops. Bad headline. Fake news!) Although Shore retired all the batters he faced, MLB eventually credited him with a no-hitter, not a perfect game.

“It was the best pitching seen in this city since 1904,” wrote the Globe’s Edward F. Martin, “when Cy Young pitched to every batter …” in the first perfect game of the 20th century.

In an interview in 1978, Shore, then 86, called the no-hitter “the easiest game I ever pitched in my life.” (The Professor, who became a sheriff in North Carolina after his playing days, died in 1980.)

After the game, Owens denied Ruth's contention that he used foul language when the Babe charged toward home plate. "His conduct was in no way justified," the umpire said, "and I cannot understand how a man who has been in the game so long as he has could have so completely lost his head."

Now there was that little matter about what to do about Ruth. Newspapers speculated the Bambino would receive a severe penalty. The Babe was the Red Sox's star attraction, and fans of the defending champions fretted that a lengthy suspension for Ruth would cripple the team’s pennant chances.

“Babe Ruth's assault upon Umpire Owens at Boston yesterday,” the Times wrote, “is but one of several such scenes on the diamond this year and many believe that the rowdy era has returned to the national game.”

Johnson initially suspended Ruth indefinitely. But after Boston owner Harry Frazee's "long-distance phone call" with the AL president, Ruth's penalty was reduced to a $100 fine and a week's suspension. "About the only explantion for Johnson's leniency in the Ruth case," a newspaper wrote, "is that pressure was brought to bear upon the president of the American League."

Even The Babe, whom the Red Sox sold to the Yankees in 1919, knew he got off easy.

“I hauled off and hit [Owens], but good," Ruth recalled in his autobiography in 1948, adding, “They’d put you in jail today for hitting an umpire.”

More must-reads:

- Witness to MLB history: 101-year-old Phil Coyne even saw 'The Babe'

- Ghost hunter: How Shoeless Joe Jackson became bartender's obsession

- The 'Active MLB strikeout leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!